Traditions take many forms. For some, it’s opening day deer camp at

the family cabin. For others, it’s meeting at the end of the year to

catch up on the season’s hunts. For Montana natives Doug Krings and Dan

McMaster, it’s been chasing critters with a stick and string. This year,

Doug, Dan, and I started a new tradition.

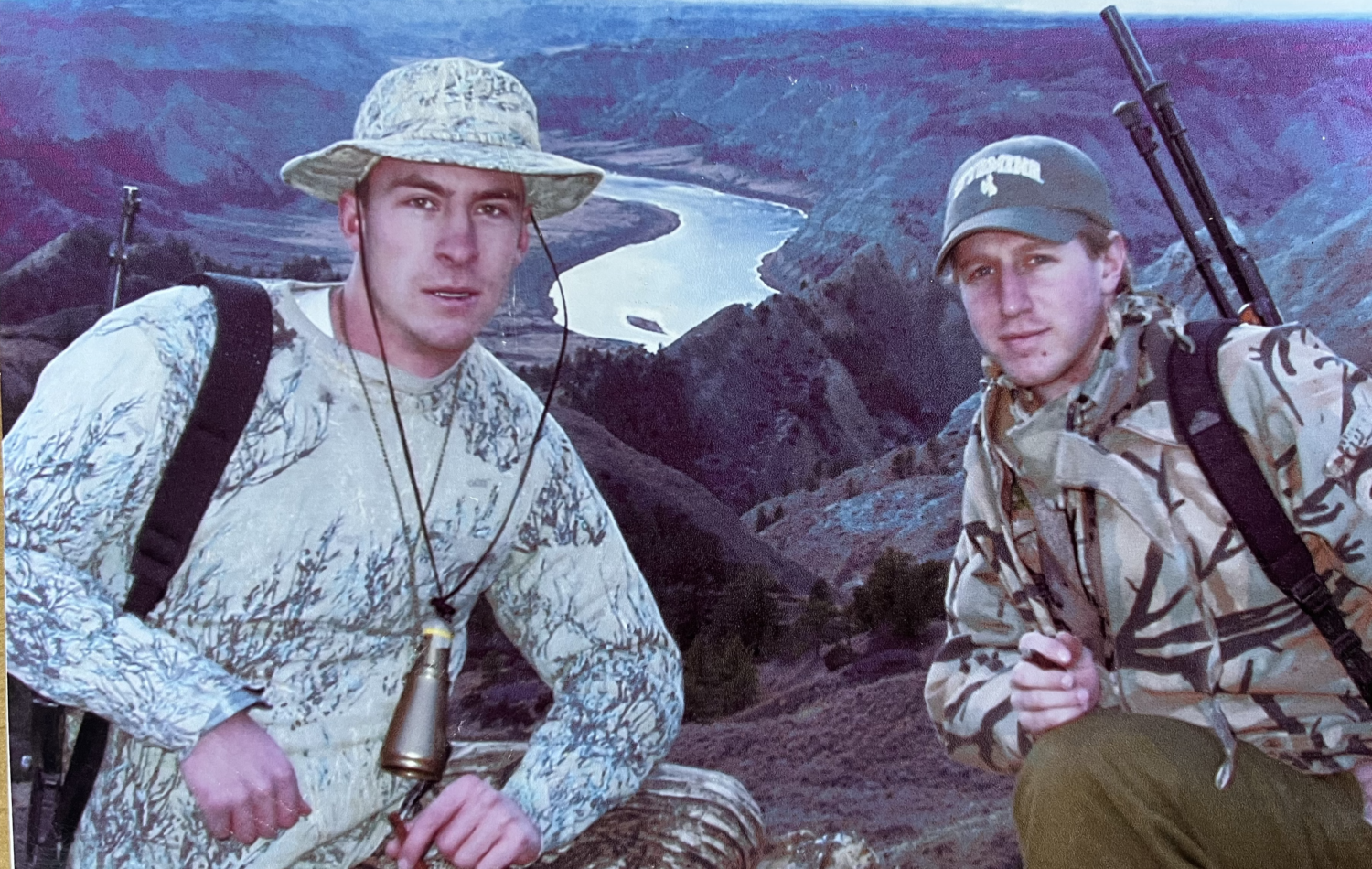

I met Doug five years ago at a Montana Backcountry Hunters and Anglers

state chapter campout. We had many mutual friends but never met each

other in person; when we did, we immediately bonded over our shared love

of shooting single-string bows. We’ve hunted deer, bears, and turkeys

together, and Doug was the person I stopped to see after I killed my

first elk with my recurve. We’ve been through the wringer in the

backcountry, and I consider Doug one of my closest friends. I met Dan

one night over a few beers while sharing hunting stories in Doug’s

living room before heading to elk camp, where we hit it off immediately.

For years, Dan fought fires for the BLM. He traveled to many states

before finally settling on a small island in Southeast Alaska. Dan has a

network of friends who hunt blacktails in Southeast Alaska, but all are

rifle hunters. Dan is a bowhunter through and through, so this year,

Dan pitched the idea of an early-season alpine traditional bow hunt for

velvet blacktails. Dan didn’t have to twist our arms–we were in.

For years, Dan fought fires for the BLM. He traveled to many states

before finally settling on a small island in Southeast Alaska. Dan has a

network of friends who hunt blacktails in Southeast Alaska, but all are

rifle hunters. Dan is a bowhunter through and through, so this year,

Dan pitched the idea of an early-season alpine traditional bow hunt for

velvet blacktails. Dan didn’t have to twist our arms–we were in.

Doug has been to Alaska for quite a few hunts, but I’ve only been

once in a completely different part of the state. We spent the summer

preparing for the trip, not knowing what a Southeast Alaska hunt would

demand from us. We shot multiple 3D archery courses, ran, and hiked with

weighted packs through the smoke of an awful fire season under the Big

Sky.

We arrived in Southeast Alaska in a stretch of uncharacteristically

beautiful weather. With a three-day window before a big front rolled in,

we dumped our bags, repacked, and put boots-to-dirt four hours after

touching down. Our packs were heavy, and our spirits were high.

We passed a group of cruise ship tourists on a stopover hike on the trail. They took photos as we clipped by.

“Are you guys hunting?” one tourist asked.

“Not yet, but we’re en route,” I replied.

“What are you hunting?” the tourist followed up.

“Deer and grouse if all goes as planned,” I said.

“Wow! With bows? Good luck!” the tourist finished, and we parted ways.

I thought about that interaction as we climbed the mountain. Such a

funny juxtaposition: a ragtag bunch of camo-clad, stick bow-toting guys

on a full-fledged do-it-yourself adventure in the Alaskan wilderness;

and groomed tourists on an ultra-pasteurized, hyper-curated cruise

“adventure.”

Onward we marched.

As we climbed, the trail changed from dirt to boardwalk. I’m still

unsure how I feel about those planks. Being elevated above the soggy

ground made for easier walking, but pounding out 2,600 feet of elevation

gain with a 60-pound pack and jarring contact on every step made you

wonder if the squishy ground wouldn’t give our hips and knees some

reprieve. After stopping for water at 1,500 feet, we donned our packs

once more and made the final push to the top.

Soon, the dense rainforest thinned as we crested into the alpine.

Miles of muskeg interspersed with patchy timber sprawled as we left the

ferns and devil’s club behind us. We slipped off our packs, set up camp,

and began glassing.

Off the west end of our perch, we glassed our first deer. A lone doe

bedded on the edge of the trees overlooking an interlocked chain of

muskeg. We saw another lone deer–a buck–bedded below a rimrock and alder

bank off the east side. We took notes as the sunset and built a fire to

get dinner rolling.

Dan packed in a bag of spot prawns he caught not far off the island

and surprised Doug and me with the delicacy around the fire. After a

whirlwind day of travel, packing, hiking, and glassing, this unexpected

treat was what campfire dreams are made of.

Another juxtaposition flooded my mind. I started my morning in an

airport with hundreds of people and processed food; I ended my day on

top of a mountain, eating spot prawns over a campfire overlooking a

saltwater bay. I’ve never described protein as sweet, but those prawns

were the sweetest and most delicious protein I’ve ever had. Soon after,

three satiated, sore, and happy hunters drifted off to sleep.

The following day we were up with the sun and put our glass to work.

Hunkered in at camp, we scoured the lush green, salad-covered hillsides

for carrot-colored bucks with velvet headgear. Almost immediately, we

started picking up deer moving across the hillsides. The number of deer

excited us, but we knew finding success was an entirely different

challenge with only bucks being legal.

Blacktails are funny creatures. They prance like a caribou across the

muskeg, moving effortlessly and silently where two-legged creatures get

swallowed by the bog. They have whitetail antlers with mule deer faces

and a gorgeous double throat patch. In the summer, they are orangish

with short, stubby legs and bodies that look like a sausage about to

burst through its casing.

We watched these Vienna sausages feed, bed, and disappear into the

thick cover across the tops of the island. Once they were out of sight,

we moved to get the wind right and still-hunt our way through the sparse

timber, hoping to catch the flick of an ear or a head turn before

getting spotted. The plan was bulletproof from a distance, but moving

quietly and slowly through the new terrain was a learning experience of

its own.

The ground was mysterious and left me with no obvious way to plan an

approach. What looked solid would swallow my leg to my crotch. What

looked soft would support two people sneaking in a line–until it

wouldn’t. We operated in a maze of guessing our next steps as we

attempted to get close to the deer. In Montana, I’m used to trying to

avoid pinecones, branches, and cactus in the final moments of a stalk.

In Alaska, I was just hoping to stay above ground.

Doug and I set out after the deer we spotted that morning while Dan

picked his way through patches of cover off the backside of our camp.

Stalk after stalk, and we’d freeze in our tracks as a doe would step out

within bow range. Only bucks are legal, so we took the time to enjoy

the encounter. Upon arrival, the bedding area looked completely

different from our morning perch.

Still-hunting our way through the alders led us to the ledge where we

watched a buck bed the night before. An almost sheer face covered in

wet vegetation was our only path down. After a hellacious approach on a

soaked cliff face, we decided to take our chances with vegetation. After

a few hours of cursing, slipping, and sliding down the mountain, we

made it to the open muskeg. Looking back up the grade, Doug and I both

questioned our sanity.

Over and over for the next three days, we repeated unsuccessful

stalks through an uncharted country. On the fourth day, the clouds

rolled in, so we decided to pack camp and try our luck on old logging

roads where we hoped to glass for deer at lower elevations between the

shifting clouds. But first, we recharged with a shower, a hot meal, and

some coastal fishing off the island.

We spent a day stocking up on salmon, halibut, prawns, and crab in

the pouring rain. Dan’s dad, Dick, was in town with his childhood friend

Olie, so we took the time to share stories, secure some food for the

trip back, and plan the last leg of the hunt.

Most of the island is public land. We scoured our maps and located a

few areas with considerable road access that allowed us to cover the

mountain from bottom to top and back down again. We chose mobility over

how remote a place was to be fluid and move with visibility. We glassed

muskegs during peak hours and still-hunted through swaths of cut timber,

trying to make the most of our time.

We pulled out all stops on the last night, still-hunting muskegs on

some public ground close to town. There was nowhere for the water to

drain down the mountain at the lower elevation, so it sat and pooled and

waited under the muskeg for an unsuspecting hunter to step and swallow

him whole. Does crossed in the distance between timber patches in the

center of the muskeg. Doug and I flanked the thick forest that formed

the fringe of the muskeg in a push reminiscent of the two-person deer

drives I did as a kid during the Pennsylvania flintlock season.

Staggered, we carefully stepped along the edges, trying to stay above

ground.

We pulled out all stops on the last night, still-hunting muskegs on

some public ground close to town. There was nowhere for the water to

drain down the mountain at the lower elevation, so it sat and pooled and

waited under the muskeg for an unsuspecting hunter to step and swallow

him whole. Does crossed in the distance between timber patches in the

center of the muskeg. Doug and I flanked the thick forest that formed

the fringe of the muskeg in a push reminiscent of the two-person deer

drives I did as a kid during the Pennsylvania flintlock season.

Staggered, we carefully stepped along the edges, trying to stay above

ground.

From across the fog, I saw Doug freeze as a doe slipped towards me. I

sank up to my knees as the doe trotted by, and a buck approached from

behind her. He stepped out at 60 yards, well out of my effective

distance, and we locked eyes. We examined each other, him moving

effortlessly across the soggy ground–me buried and stuck. He floated

away silently as I wiggled my way out of the earth and walked back to

the truck with Doug under the cover of darkness.

We ate halibut, spot prawns, and crab back at the house. We shared

stories from the trip, from hunts gone by, and plotted what we’d do

differently the next time we chased blacktails in Southeast Alaska. The

night disappeared, as did the food and a few beers, and I thought about

crossing paths with the tourist at the trailhead.

‘Good luck!’ rang in my head. So many close calls and almosts; we

couldn’t get close enough to close the deal, and we were leaving tired

and battered. But looking around, I couldn’t help but be grateful for

how lucky I was–for these people, for this place, for these experiences

and lessons learned, and for this new tradition. Because the best part

about building a tradition is knowing there is always next year.

LOCATED IN MISSISSAUGA ONTARIO CANADA

LOCATED IN MISSISSAUGA ONTARIO CANADA

EASY & SECURE PAYMENT METHODS

EASY & SECURE PAYMENT METHODS

FAST TURNAROUND TIMES

FAST TURNAROUND TIMES